Did you see Dan Baldassarre’s wonderful paper entitled “What’s the Deal with Birds?” published on April 1 (!) last year? If not, you’re in for a treat. Dan did something that I had been thinking of for quite a while, namely to reply to one of the countless requests for manuscripts that he, I, and probably most scientists who have ever published anything, receive from predatory journals. He decided to write up some crap, submit it, and try to get it published, to prove a point. You can retroactively follow the whole saga in his Twitter thread, and very well-deserved, the story received quite a bit of attention. And what’s not to like? Dan concluded that birds are weird, and a partial result was that penguins look like fish (weird).

Figure 1 from Baldassarre (2020).

Well, like I said, I had been planning on doing something similar for quite a while and discussed it with my friend Danny Haelewaters. Since I am an ornithologist who, at the time, worked on fish, and since Danny is a mycologist, we thought that Dan Baldassarre’s initial explorations were noteworthy, but felt that they could be expanded and go deeper. Thus, we embarked on a truly interdisciplinary collaboration that made use of cutting-edge methodology, and we could expand Dan Baldassarres’s observation quite dramatically:

As the attentive reader will have seen, we can draw several conclusions from our study. As a side result, it turns out that barn swallows and flying fish are sister lineages (quite the taxonomic earthquake!). For the main result, we predict that penguins will re-evolve flight as poisonous fungi colonize the Antarctic, if the temperature rises, and this decreased fishiness will increase the chances of you ordering a penguin pizza in the future! Didn’t quite catch that? Well, read our ground-breaking paper, and as a bonus you might pick one or two hints at the publishing industry (and other things)!

Writing this paper was fun and quick, and it has been accepted for publication in multiple journals. However, we were less successful than Dan Baldassarre at haggling to get it published without paying the ridiculous publication fees that makes up the core of the business model for predatory journals. So, it has taken until now to finally get this paper published, but along the way, we have received some golden nuggets, such as this “peer review report” from the Journal of Ecosystems and Ecography:

Our paper is now out in the Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal, published by predatory Juniper Publishers. So what—and why? I am sure that some of you will think this is just rubbish, and that’s fine. Some might even find it NOT funny, or perhaps even vulgar. Well, I think that our paper very clearly demonstrates the total lack of review and the sole interest of profiting on authors that the predatory journal industry rests upon.* We further intend to deal with this in a more formal and serious manner, using our fishy bird paper as an example. Keep your eyes open for that!

Reference: Stervander M & Haelewaters D. 2020. Fishiness of piscine birds linked to absence of poisonous fungi but not pizza. Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal 12(5): 555850. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2020.12.555850.

Update 1: We do not regret the least that our reference no. 4 is no longer available on its original platform.

Update 2: *Does this work? What have other attempts looked like? Zen Faulkes have collected and curated “sting papers” such as ours in an online volume, Stinging the Predators—A collection of papers that should never have been published. This collection comprises 340 pages worth of sting papers and analysis. We are, of course, happy that our paper has been included as no. 33 in version 17 of this freely available resource!

Update 3: Sam Perrin has written a blog post at Ecology for the Masses, where he broke down our paper “for the benefit of those outside the scientific community who may not understand complex jargon like ‘pizza toppingness’ and ‘random selection by dart'”. We’re talking serious #SciComm here! Also (as can be seen in the comments below), Jerry Coyne has written a blog post about our paper, commenting more generally on hoax/sting papers and predatory journals.

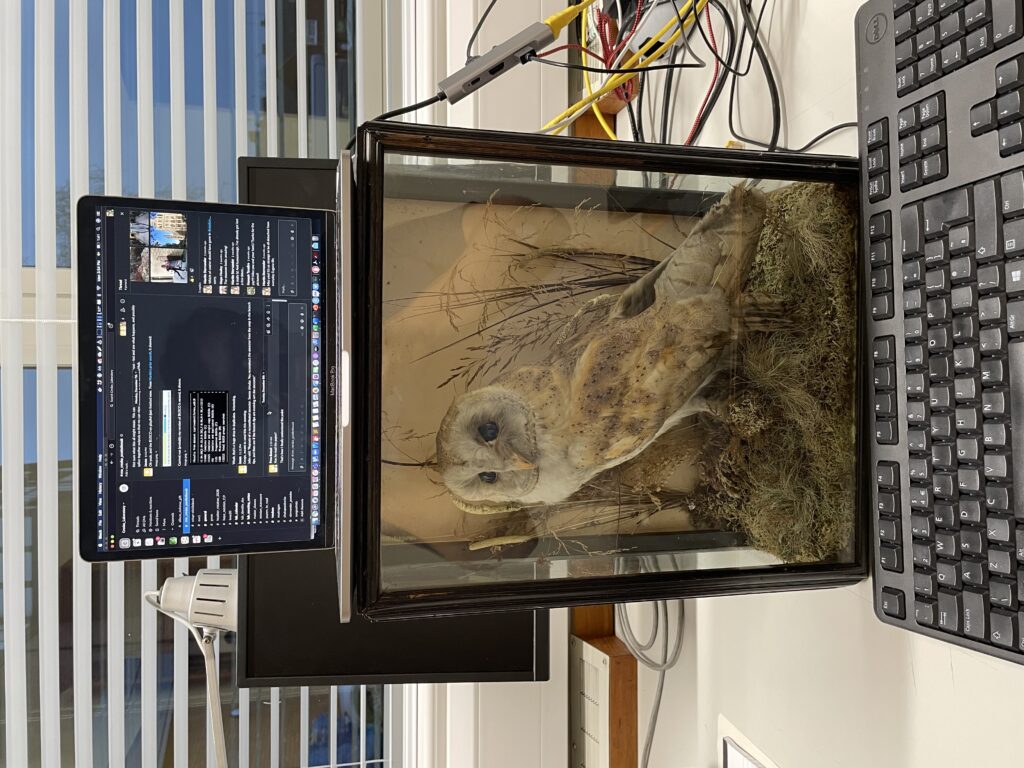

My project FLIGHTLOSS aims to uncover the genomic architecture of convergent loss of flight in rails. But there’s more to research than the research, and there are more career paths than being a university professor. I have the benefit of carrying out my project at the Natural History Museum, which houses one of the (two) largest bird collections in the world (the other one being the American Museum of Natural History). The bird collection is at NHM’s branch in Tring, northwest of London, and comprises a mind-blowing >1,000,000 specimens! I am a member of the Bird Group, which—you guessed it—cares for the ornithological collections. It currently consists of six permanent curatorial staff; all with their own specialty. Because what is in the collection? Stuffed birds, right? Nope, it’s quite a lot more diverse than that. The majority of the specimens in collection, about a quarter million, are indeed skins (“stuffed birds”). But there are also 20,000 skeletons, 20,000 spirit specimens (“pickles”), 300,000 egg clutches, and 4,000 nests!

My project FLIGHTLOSS aims to uncover the genomic architecture of convergent loss of flight in rails. But there’s more to research than the research, and there are more career paths than being a university professor. I have the benefit of carrying out my project at the Natural History Museum, which houses one of the (two) largest bird collections in the world (the other one being the American Museum of Natural History). The bird collection is at NHM’s branch in Tring, northwest of London, and comprises a mind-blowing >1,000,000 specimens! I am a member of the Bird Group, which—you guessed it—cares for the ornithological collections. It currently consists of six permanent curatorial staff; all with their own specialty. Because what is in the collection? Stuffed birds, right? Nope, it’s quite a lot more diverse than that. The majority of the specimens in collection, about a quarter million, are indeed skins (“stuffed birds”). But there are also 20,000 skeletons, 20,000 spirit specimens (“pickles”), 300,000 egg clutches, and 4,000 nests!

Most bird specimens in museum collections are prepared as study skins, i.e. they look like birds lying flat on their back. In order to obtain a tissue sample for DNA extraction, while causing minimal damage to the specimen, the most common method is to cut thin scrapes of dermal tissue from a toepad. For my EU-funded FLIGHTLOSS project, I have obtained such samples from several rail species, and additionally I have processed other samples for some exciting side projects.

Most bird specimens in museum collections are prepared as study skins, i.e. they look like birds lying flat on their back. In order to obtain a tissue sample for DNA extraction, while causing minimal damage to the specimen, the most common method is to cut thin scrapes of dermal tissue from a toepad. For my EU-funded FLIGHTLOSS project, I have obtained such samples from several rail species, and additionally I have processed other samples for some exciting side projects.  Under the guidance of Dr. Martin Irestedt, I have learnt to implement the local flavor of best practices and protocols for work with toepad samples. In short, in a clean lab (protected from the contamination of DNA from any modern source) I have extracted DNA. Unlike from fresh tissue, the DNA in historic specimens is degraded and broken up in small fragments. I have sorted out fragments of an appropriate length and turned them into libraries, which will be sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq, which spits out millions and millions of sequence reads. These can then be stitched together against the reference genome of a closely related species.

Under the guidance of Dr. Martin Irestedt, I have learnt to implement the local flavor of best practices and protocols for work with toepad samples. In short, in a clean lab (protected from the contamination of DNA from any modern source) I have extracted DNA. Unlike from fresh tissue, the DNA in historic specimens is degraded and broken up in small fragments. I have sorted out fragments of an appropriate length and turned them into libraries, which will be sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq, which spits out millions and millions of sequence reads. These can then be stitched together against the reference genome of a closely related species. All in all, the visit was very successful, and I managed to create sequencing libraries from 48 out of 49 samples. Working with historical samples, there’s always a bit of randomness included, and usually one would expect more than one sample out of fifty to fail, so I am stoked! I am extra happy and proud to have successfully extracted DNA from an extinct parakeet, which was collected in the 1770 on one of Captain Cook’s journeys.

All in all, the visit was very successful, and I managed to create sequencing libraries from 48 out of 49 samples. Working with historical samples, there’s always a bit of randomness included, and usually one would expect more than one sample out of fifty to fail, so I am stoked! I am extra happy and proud to have successfully extracted DNA from an extinct parakeet, which was collected in the 1770 on one of Captain Cook’s journeys. *The bulk of my samples were sent by courier from the UK and should have arrived before me. Instead, the courier screwed up, and I spent days waiting for the samples to arrive. But I couldn’t just reschedule my trip back, so let’s just say I din’t see much more than the lab in Stockholm.

*The bulk of my samples were sent by courier from the UK and should have arrived before me. Instead, the courier screwed up, and I spent days waiting for the samples to arrive. But I couldn’t just reschedule my trip back, so let’s just say I din’t see much more than the lab in Stockholm.

If you learned your birds some 10–20 years ago or earlier, you will know that lots of (annoying?) rearrangements and reclassifications have happened lately. This is because traditional taxonomy often sorted birds into large, ecologically-based groups, like warblers or finches, since the morphological differences were relatively small. Over the past couple of decades, DNA-based studies have revealed time and time again that these relationships were not what we thought. Here, we try to set the record straight, and propose a new classification and linear taxonomy based on the evolutionary history of passerines.

If you learned your birds some 10–20 years ago or earlier, you will know that lots of (annoying?) rearrangements and reclassifications have happened lately. This is because traditional taxonomy often sorted birds into large, ecologically-based groups, like warblers or finches, since the morphological differences were relatively small. Over the past couple of decades, DNA-based studies have revealed time and time again that these relationships were not what we thought. Here, we try to set the record straight, and propose a new classification and linear taxonomy based on the evolutionary history of passerines.